Bram Stoker – The Primrose Path

— — —

“Jerry laughed – the hard, cold laugh of a demon. ‘Time for you to sell it.’“

— — —

“The Primrose Path“ is a novel written by Bram Stoker. It is a ten chapters long and focuses on the evils of drinking.

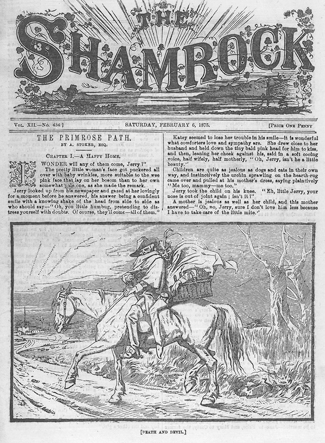

“The Primrose Path” was Stoker’s first novel and was published 22 years before Dracula. It was serialized in The Shamrock in five installments from February 6, 1875 to March 6, 1875.

This article features a complete, embedded, mobile-friendly version of “The Primrose Path“ by Bram Stoker as well as a text version below.

The Primrose Path – PDF

A PDF copy of “The Primrose Path” can be downloaded using the menu in the embedded reader below.

The Primrose Path – Mobile Friendly

— — —

The Primrose Path

by

Bram Stoker

— — —

CHAPTER 1

A Happy Home

‘I wonder will any of them come, Jerry?’

The pretty little woman’s face got puckered all over with baby wrinkles, more suitable to the wee pink face that lay on her bosom than to her own somewhat pale one, as she made the remark.

Jerry looked up from his newspaper and gazed at her lovingly for a moment before he answered, his answer being a confdent smile with a knowing shake of the head from side to side as who should say – ‘Oh, you little humbug, pretending to distress yourself with doubts. Of course, they’ll come – all of them.’

Katey seemed to lose her trouble in his smile – it is wonderful what comforters love and sympathy are. She drew close to her husband and held down the tiny bald pink head for him to kiss, and then, leaning her cheek against his, said in a soft cooing voice, half wifely, half motherly, ‘Oh, Jerry, isn’t he a little beauty.’

Children are quite as jealous as dogs and cats in their own way, and instinctively the urchin sprawling on the hearth-rug came over and pulled at his mother’s dress, saying plaintively ‘Me too, mammy – me too.’

Jerry took the child on his knee. ‘Eh, little Jerry, your nose is out of joint again; isn’t it?’

A mother is jealous as well as her child, and this mother answered – ‘Oh, no, Jerry, sure I don’t love him less because

I have to take care of the little mite.’

Further conversation was stopped by a knock at the door. ‘That’s some of them stayin’ away,’ said Jerry, as he went

out to open the door.

As may be seen, Jerry and his wife expected company, the doubts as to whose arrival was caused by the extreme inclemency of the weather, and as the occasion of the festivities was an important one, the doubts were strong.

Jerry O’Sullivan was a prosperous man in his line of life. His trade was that of a carpenter, and as he had, in addition to large practical skill and experience gained from unremitting toil, a considerable share of natural ability, was justly considered by his compeers to be the makings of a successful man.

Three years before he had been married to his pretty little wife, whose sweet nature, and care for his comfort, and whose desire to perfect the cheerfulness of home, had not a little aided his success, and kept him on the straight path.

If every wife understood the merits which a cheerful home has above all other places in the eyes of an ordinary man, there would be less brutality than there is amongst husbands, and less hardships and sufering amongst wives.

The third child has just been christened, and some friends and relatives were expected to do honour to the occasion, and now the knock announced the frst arrival.

Whilst Jerry went to the door, Katey arranged the child’s garments so as to make him look as nice as possible, and also fxed her own dress, somewhat disturbed by maternal

cares. In the meantime little Jerry fattened his nose against the window pane in a vain desire to see the appearance of the frst arrival. Little Katey stood by him looking expectant as though her eyes were with her brother’s.

Mrs Jerry’s best smile showed that the newcomer, Mr Parnell, was a special friend. After shaking hands with him she stood close to him, and showed him the baby, looking up into his dark strong face with a smile of perfect trust. He was so tall that he had to stoop to kiss the baby, although the little mother raised it in her arms for him. He said very tenderly –

‘Let me hold him a minute in my arms.’

He lifted him gently as he spoke, and bending his head, said reverently: –

‘God bless him. Sufer little children to come unto me, for of such is the kingdom of Heaven.’

Katey’s eyes were full of tears as she took him back, and she thanked the big man with a look too full of sacred feeling for even a smile.

Jerry stood by in silence. He felt much, although he did not know what to say.

Another knock was heard, and again Jerry’s services were required. This time there was a large infux, for three diferent bodies had joined just at the door. Much laughter was heard in the hall, and then they all entered. The body consisted of seven souls all told.

Place aux dames. We Irishmen must give frst place always to the ladies. Of these there were four. Jerry’s

mother and her assistant, Miss M’Anaspie, and Katey’s two sisters, one older and one younger than herself. The men were, Mr Muldoon, Tom Price, and Patrick Casey.

Jerry’s mother was a quiet dignifed old lady, very gentle in manner, but with a sternness of thought and purpose which shone through her gentleness and forbid any attempt at imposition, as surely as the green light marks danger at a railway crossing. She had a small haberdashery shop, by which she was reputed amongst her friends to have realised a considerable amount of money. Miss M’Anaspie was her assistant, and was asked by Katey to be present out of pure kindness. She had originally set her cap at Jerry, and had very nearly succeeded in her aim. It was no small evidence of Katey’s genuine goodness of nature and her perfect trust of her husband that she was present; for most women have a feeling of possible hostility, or, at least, maintain an armed neutrality towards the former fames of the man that they love. Miss M’Anaspie was tall and buxom, and of lively manners, quite devoid of bashfulness. It puzzled many of her friends how, with her desire to be married, she had not long ago succeeded in accomplishing her wish. Katey’s sisters were pleasant, quiet girls, both engaged to be married – Jane to Price, and Mary to Casey, the former man being a blacksmith, and the latter an umbrella-maker, both being sturdy young fellows, and looking forward to being shortly able to marry.

Mr Muldoon was the great man of the occasion. He was a cousin of Mrs O’Sullivan’s, and was rich. He had a large Italian warehouse, which he managed well, and

consequently was exceedingly prosperous. Personally he was not so agreeable as he might have been. He was small, and stout, and ugly, with keen eyes, a sharply-pointed nose; was habitually clean-shaven, and kept his breast stuck out like that of a pouter pigeon. He always dressed gorgeously, and on the present occasion, as he considered that he was honouring his poor relations, had got himself up to a pitch of such radiance that his old servant had commented on his appearance as he had left home. His trousers were of the lightest yellow whipcord; his coat was blue; his waistcoat was red velvet, with blue glass buttons; and in the matter of green tie, high collar, and large cufs he excelled. His watch chain, of massive gold, with the ‘pint of seals’ attached to the fob-chain after the manner of the bucks of the last generation was alone worthy of respect. His temper was not pleasant, for he was dictatorial to the last degree, and had a very unpleasant habit, something like Frederick the Great, of considering any diference of opinion as an insult intentionally ofered to himself.

A man like this may be a pleasant enough companion so long as he goes with the tide, he thinking that it is the tide which goes with him; but when occasion of diference arises, the social horizon at once becomes overcast with angry clouds which gather quickly till the storm has burst. Oftentimes, as in nature – the great world of elements – the storm clears the air.

Mr Muldoon had been asked as an act possibly likely to beneft the new olive branch, for the Italian grocer was unmarried, and might at some future time, so thought Jerry

and Katey in their secret hearts, take in charge the destinies of the new infant to-day made John Muldoon O’Sullivan.

When the party entered the room Mr Muldoon had advanced to Mrs Jerry, and, as she was a pretty little woman, had kissed her in a semi-paternal way which made Miss M’Anaspie giggle. Mr Muldoon looked round half indignantly, for he felt that his dignity was wounded. He considered that Miss M’Anaspie, of whose very name he was ignorant, was a forward young person, and in his mind determined to let her understand so before the evening was over.

After a few minutes the introductions had all been accomplished, and everybody knew everybody else. There was great kissing of the baby, great petting of the two elder children, for whose delectation sundry sweets were produced from mysterious pockets, and much laughter and good-humoured jesting.

Mr Muldoon prided himself upon being a good hand at saying smart things, and felt that the present occasion was not one to be thrown away. Being a bachelor, he considered that his most proper attitude was that of ignorance – utter ignorance regarding babies in general, and this one in particular. When he was shown the baby he put up his eyeglass, and said:

‘What is this?’

‘Oh, Mr Muldoon,’ said the mother, almost reproachfully. ‘Sure, don’t you know this is the new baby?’

‘Oh! oh! indeed. It is very bald.’

‘It won’t be long so, then,’ interrupted Miss M’Anaspie pertly. You can make it your heir, if you will.’ Her English method of aspiration pointed the joke.

Mr Muldoon looked at her almost savagely, but said nothing. He did not want to commit himself to any intention of aiding the child’s career; and he was obliged to remain silent. He mentally scored another black mark against the speaker.

Presently he spoke again.

‘Is it a boy or a girl?’

‘A boy.’

‘And are these boys or girls?’ He pointed as he spoke to little Jerry and little Katey.

Miss M’Anaspie answered again— ‘Neither. They are half of each.’

‘Dear me,’ said Mr Muldoon. ‘Can that be?’

‘Don’t you see,’ said Miss M’Anaspie in a tone which implied the addition of the words ‘you silly old fool,’ ‘one is a boy and the other a girl.’

Mr Muldoon made another black mark in his mental note-book, and ignoring his opponent, as he already considered Miss M’Anaspie, spoke again to Katey.

‘And are these all yours? Three children; and you have been married – let me see, how long?’

‘Three years and two months.’

‘Why, at this rate, what will you do in twenty years. Just fancy twenty children. Really, Mrs Katey, you should take the pledge.’

Katey did not know what to answer, and so stayed silent. Miss M’Anaspie turned away to hide an imagined blush, and Mr Muldoon feeling that he had said something striking, began to unbend and mix with the rest of the company in a better humour than he had been in for some time.

The table was ready set with all the materials for comfort, and as the teapot was basking inside the fender beside a dish of highly buttered cake, the work of Mrs Jerry herself, and the kettle singing songs of a bacchanalian character on the fre, promise of comfort to the foes and friends of Father Mathew was not wanting.

There was great arranging of places at the table. Jane and Mary with their sweethearts managed to monopolise one entire side, sitting alternately like the bread and ham in the pile of sandwiches before them.

Mr Muldoon was put next to Katey, and Jerry had his mother on his right hand, she being supported on the other side by Mr Parnell. This left Miss M’Anaspie to take her seat without choice, between the two eldest men of the party.

She did not shrink from the undertaking, however, but sat down, saying pertly to the company, but to no one in particular –

‘My usual luck. Never mind. I like to have an old man on each side of me.’

Mr Muldoon liked to be thought young – most middle-aged bachelors do – and he looked his disapprobation of the remark so strongly that a silence fell on all.

The dowager Mrs O’Sullivan said quietly –

‘You let your tongue run too fast, Margaret. You forget Mr Muldoon is a new friend of yours, and not an old one.’

Miss M’Anaspie had already seen that she had made a mistake, and was only waiting for an opportunity of correcting it, so she seized it greedily.

‘I am so awfully sorry. I hope, sir, I did not ofend. Indeed I wished to please. I thought that young people wished to be thought old. I know that I did when I was young.’

‘That was some time ago,’ whispered Pat Casey to Mary, who laughed too suddenly, and was nearly caught at it.

Mr Muldoon was mollifed. He thought to himself that perhaps the poor girl did not mean to give ofence; that she was a clever girl; much nicer after all than most girls; however that he would have an eye on her, and see what she was like.

For some time the consumption of the good things occupied the attention of everybody. Mrs Jerry handed a cup of tea to Mr Parnell before any of the rest of the men, saying –

‘I know you like that better than anything else.’

‘That I do,’ he answered heartily. ‘There is as much virtue in this as there is evil in beer, and whisky, and gin, and all other abominations.’

No one felt inclined to take up, at present at all events, the total-abstinence glove thus thrown down, and so the subject dropped.

It would have done one good to have seen the care which Katey’s sisters took of their sweethearts, piling up their

plates with everything that was nice, and keeping them as steadily at work as if they had been engaged in a contest as to who should consume the largest quantity in the smallest time. This was a species of friendly rivalry in which the men found equal pleasure with the girls.

It is quite wonderful the diference between the appetites of successful and unsuccessful lovers.

Mr Muldoon and Miss M’Anaspie during the progress of the meal became fast friends, at least so it would seem, for they bandied, unchecked, pleasantries of a nature usually only allowed amongst intimate friends. Both Jerry and his wife were much amazed, for both stood somewhat in awe of the great man with whom they would never have attempted to make any familiarity.

By the time the heavy part of the eating was done, the whole assemblage was in hearty good humour.

Katey began to clear away the things, having given the baby in charge to her mother-in-law. The moment she began, however, Mary and Jane started up and insisted that they should do the work, and on her showing signs of determination forced her into the arm-chair, and placed the two sweethearts on guard over her, threatening them with various pains and penalties in event of their failing in their trust.

Seeing the other girls at work, Miss MAnaspie insisted on helping also, and they were too kind-hearted not to make her welcome in the little kindly ofice.

The next addition to the working staf was Mr Muldoon, who, to the astonishment of every one who knew him,

clamoured loudly for work, evidently bent on going wherever Miss M’Anaspie went, and on helping her in her every task.

It was a sight to see the great man work. He evidently felt that he was extending and being more friendly with his inferiors than, perhaps, in justice to his own position he was warranted in doing; and he took some pains to let every one see that he was playing at work. His ignorance of the simplest domestic ofices was preternatural. He did not know how to carry even a plate without putting it somewhere he ought not, or spilling its contents over some one; and he managed to break a tumbler and two plates just to show, like Beaumarchais and the watch, that that sort of thing was not in his line.

Mrs Jerry did not know Pope’s lines about the perfection of a woman’s manner and temper, wherein he puts as the culmination of her virtues, ‘And mistress of herself though china fall;’ but she had the good temper and the good manner of nature, which is above all art, and although, woman-like, the wreck of her household goods went to her heart, she said nothing, but looked as sweet as if the breakage pleased her.

Truly, Jerry O’Sullivan had a sweet wife and a happy home. Prosperity seemed to be his lot in life.

CHAPTER 2

To And Fro

When all was made comfortable for the after sitting, the conversation grew lively. The position of persons at table tends to further cliquism, and to narrow conversation to a number of dialogues, and so the change was appreciated.

The most didactic person of the company was Mr Parnell, who was also the greatest philosopher; and the idea of general conversation seemed to have struck him. He began to comment on the change in the style of conversation.

‘Look what a community of feeling does for us. Half an hour ago, when we were doing justice to Mrs O’Sullivan’s good things, all our ideas were scattered. There was, perhaps, enough of pleasant news amongst us to make some of us happy, and others of us rich, if we knew how to apply our information; but still no one got full beneft, or the opportunity of full beneft, from it.’

Here Price whispered something in Jane’s ear, which made her blush and laugh, and tell him to ‘go along.’

Parnell smiled and said gently –

‘Well, perhaps, Tom, some of the thoughts wouldn’t interest the whole of us.’

Tom grinned bashfully, and Parnell reverted to his theme. He was a great man at meetings, and liked to talk, for he knew that he talked well.

‘Have any of you ever looked how some rivers end?’

‘What end?’ asked Mr Muldoon, and winked at Miss M’Anaspie.

‘The sea end. Look at the history of a river. It begins by a lot of little streams meeting together, and is but small at frst. Then it grows wider and deeper, till big ships mayhap can sail in it, and then it goes down to the sea.’

‘Poor thing,’ said Mr Muldoon, again winking at Margaret.

‘Ay, but how does it reach the sea? It should go, we would fancy, by a broad open mouth that would send the ships out boldly on every side and gather them in from every point. But some do not do so – the water is drawn of through a hundred little channels, where the mud lies in shoals and the sedges grow, and where no craft can pass. The river of thought should be an open river — be its craft few or many — if it is to beneft mankind.’

Miss M’Anaspie who had, whilst he was speaking, been whispering to Mr Muldoon, said, with a pertness bordering on snappishness:

‘Then, I suppose, you would never let a person talk except in company. For my part, I think two is better company than a lot.’

‘Not at all, my dear. The river of thought can fow between two as well as amongst ffty; all I say is that all should beneft.’

Here Mr Muldoon struck in. He had all along felt it as a slight to himself that Parnell should have taken the conversational ball into his own hands. He was himself extremely dogmatic, and no more understood the

diference between didacticism and dogmatism than he comprehended the meaning of that baphometic fre-baptism which set the critics of Mr Carlyle’s younger days a-thinking.

‘For my part,’ said he, ‘I consider it an impertinence for any man to think that what he says must be interesting to every one in a room.’

This was felt by all to be a home thrust at Parnell, and no one spoke. Parnell would have answered, not in anger, but in good-humoured argument, only for an imploring look on Katey’s face, which seemed to say as plainly as words –

‘Do not answer. He will be angry, and there will only be a quarrel.’

And so the subject dropped.

The men mixed punch, all except Mr Muldoon, who took his whisky cold, and Parnell, who took none. The former looked at the latter with a sort of semi-sneer, and said –

‘Do you mean to say you don’t take either punch or grog?’

‘Well,’ said Parnell, ‘I didn’t mean to say it, but now that you ask me I do say it. I never touch any kind of spirit, and, please God, I never will.’

‘Don’t you think,’ said Muldoon, ‘that that is setting yourself above the rest of us a good deal. We’re not too good for our liquor, but you are. That’s about the long and the short of it.’

‘No, no, my friend, I say nothing of the kind. Any man is too good for liquor.’

Jerry thought the conversation was getting entirely too argumentative, so he cut in –

‘But a little liquor needn’t be bad for a chap if he doesn’t take too much?’

‘Ay, there it is,’ said Parnell, ‘if he doesn’t take too much. But he does take too much, and the end is that it works his ruin, body and soul.’

‘Whose?’

It was Miss M’Anaspie who asked the question, and it fell like a bombshell.

Parnell, however, was equal to the emergency.

‘Whose?’ he repeated. ‘Whose? Everyone’s who begins and doesn’t know where he may leave of.’

Miss M’Anaspie felt that she was answered, and looked appealingly at Mr Muldoon, who at once came to the rescue.

‘Everyone is a big word. Do you mean to tell me that every man that drinks a pint of beer or a glass of whisky, goes straight to the devil?’

‘No, no; indeed I do not. God forbid that I should say any such thing. But look how many men that mean only to take one glass, are persuaded to take two, and then the wits begin to go, and they take three or four, and fve, ay, and more, sometimes. Why, men and women’ – he rose from his chair as he spoke, with his face all aglow, with earnestness and belief in his words, ‘look around you and see the misery that everywhere throngs the streets. See the pale, drunken, wasted-looking men, with sunken eyes, and slouching gait. Men that were once as strong and hard-working, and

upright as any here, ay, and could look you in the face as boldly as any here. Look at them now! Afraid to meet your eyes, trembling at every sound; mad with passion one moment and with despair the next.’

The tide of his thought was pouring forth with such energy that no one spoke; even Mr Muldoon was afraid at the time to interrupt him. He went on:

‘And the women, too, God help us all. Look at them and see what part drink plays in their wretched lives. Listen to the laughter and the cries that wake the echoes in the streets at night. You that have wives, and mothers and,’ (this with a glance at Tom and Pat) ‘sweethearts, can you hear such laughter and cries and not shudder? If you can, then when next you hear it think of what it would be for you to hear some voice that you love raised like that.’

Mr Muldoon could not stand it any longer and spoke out: ‘But come now, I can’t see how all the misery and wretchedness of the world is to be laid on a simple glass of

beer.’

‘Hear, hear,’ said Miss M’Anaspie.

Parnell’s reply was allegorical. ‘Do you see how the oak springs from the acorn – the bird from the egg? I tell you that if there were no spirits there would be less sin, and shame, and sorrow than there is.’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Muldoon. ‘It would be a beautiful world entirely, and everybody would have everything, and nobody would want nothing, and we’d all be grand fellows. Eh, Miss Margaret, what do you think?’

‘Hear, hear,’ said Miss M’Anaspie, more timidly than before, however, at the same time looking over at Mrs O’Sullivan, who was looking not too well pleased at her.

‘Ah, sir,’ said Parnell, sadly, ‘God knows that we, men and women, are not what we ought to be, and sin will be in the world, I suppose, till the time that is told. But this I say, that drink is the greatest enemy that man has on earth.’

‘Why, you’re quite an enthusiast,’ said Mr Muldoon; ‘one would think you were inspired.’

‘I would I were inspired. I wish my voice was of gold, and that I could make men hear me all over the world, and that I could make the stars ring again with cries against the madness that men bring upon themselves.’

‘Upon my life,’ said Mr Muldoon, ‘you should be on the stage. You have missed your vocation. By the way, what is your vocation?’

‘I am a hatter.’

Miss M’Anaspie blurted out suddenly, ‘Mad as a hatter,’ and then suddenly got red in the face, and shut up completely as she saw her employer’s eye fxed on her with a glare almost baleful in its intensity.

Mr Muldoon laughed loudly, and slapped his fat knees as he ejaculated – ‘Brayvo, brayvo. One for his nob – mad as a hatter. That accounts for the enthusiasm.’ Then, seeing a look of such genuine pain on Katey’s face that even his obtuseness could not hide from him how deeply he was hurting her, added – ‘Of course, Mr Parnell, I am only joking; but still it is not bad – mad as a hatter. Ha, ha!’

No one said anything more, and no one laughed; and so the matter was dropped.

Jerry felt that a gloom had fallen on the assemblage, and tried to lift it by starting a new topic.

‘Do you know,’ said he, ‘I had a letter from John Sebright the other day, and he tells me if you want to make money England’s the place.’

‘Indeed,’ said his mother, satirically.

Going to England was an old ‘fad’ of Jerry’s, and one which had caused his mother many an anxious hour of thought, and many a sleepless night.

‘Yes,’ answered Jerry, ‘he says there is more work there than here, and better paid; and that a man has ten chances for gettin’ on for one he has here.’

‘The one chance often wins when the ten fail,’ said Parnell.

‘And it’s worse losing ten pounds than one,’ added Margaret.

‘And some girls’ tongues are as long as ten,’ said Mrs O’Sullivan, who could not bear anything which tended to make light of her wishes with regard to Jerry, and so determined to put a stop to Miss M’Anaspie’s volubility.

Mr Muldoon, however, came to the rescue.

‘And some girls who have been for ten years in misery and discomfort fnd sometimes that one year brings them all they want.’

Miss M’Anaspie put her handkerchief before her face, and again dead silence fell on the assembly. Parnell broke it.

‘Jerry, put the idea out of your head. You know that you couldn’t go now even if you wanted, and there is no use sighing for what can’t be.’

‘I don’t know that,’ said Jerry argumentatively. ‘I could go now with Katey and the young ones, just as well as if I was a boy still; ay, and better, for she would keep me out of harm.’

Parnell said with great feeling, ‘That’s right, Jerry; stick up for the wife and stick to her too, for she’s worth it. Do you but keep to your wife, and the home that she will always make for you, as long as you let her, and you may go when and where you will, and your hands will fnd work.’

Katey began to cry. She was still a little delicate, and anything which touched her feelings upset her very much. There was an immediate rush of all the women in the room to comfort her.

Jerry ofered her some of his punch, but she put the glass aside, saying –

‘No, no, dear, I never take it.’

‘Come, come,’ said Mr Muldoon, ‘Mrs Katey, this will never do, you must take it. It is good for you.’

‘No, it is good for no one.’

‘Come now, Mr Parnell,’ said Mr Muldoon, ‘don’t you know a sup of liquor would do her good? Tell her so.’

‘No, no,’ said Katey, ‘I know myself.’ Parnell spoke –

‘I cannot say, but it is good as a medicine, and as a medicine one may take it without harm.’

‘Capital thing to be sick sometimes,’ said Muldoon, winking at Tom and Pat, and laughing at his own joke.

Parnell did not like to let a point go unquestioned on a subject on which he felt deeply, so he answered –

‘When you are sick, your wish is to be well again, and the medicine that seems nice to you when well, is only in sickness but medicine after all.’

Once more Mr Muldoon began to get angry, and said, with a determination to fght the argument – a I’outrance-

‘Why, man, you would make the world a hell with all your self-denials. Do you think life would be worth having if every enjoyment of it, great and little, was to be suppressed. The world is bad enough, goodness knows, already, without making a regular hell of it.’

‘Hell is a big word.’

‘It is a big word, and I mean it to be a big word.’

‘Ah, it is like enough to hell already,’ said Parnell sadly. ‘On account of all the bad spirits,’ added Miss

M’Anaspie.

‘Laugh, my child. Laugh whilst you may. Heaven grant that the day may never come when you cannot laugh at such thoughts. Ay, truly, the world is hard enough as it is. Bad enough, and the devil is abroad enough, and too much.’

‘Oh, he’s on earth is he?’

‘Yes, Mr Muldoon, he is, to and fro, he walks always.’ Whilst he was speaking he was drawing in his note-book. Miss M’Anaspie got curious to know what he was doing,

and asked him.

In reply he handed her the book.

She took it eagerly, and then passed it on to all the others in turn.

He had drawn an allegorical picture under which he had written – ‘To and Fro.’

The picture represented a road through a moor to a village, seen lying some distance away, the spire of its church shadowed by a passing cloud. The moor was bleak, with, in the foreground, a clump of blasted trees, and in the distance a ruined house. On the road two travellers were journeying, both seated on the same horse – a sorry nag. One of them was booted and spurred, and wore a short cloak, a slouched hat, under which the lineaments showed ghastly, for the face was but that of a skull. The other, who rode pick-a-back, was clad as the German romances love to clothe their demon when he walks the earth, with trunk hose and pointed shoes, a long foating cloak, and peaked cap with cock’s feathers. On his arm he bore a basket full of bottles, and as he clutched his grisly companion he laughed with glee, bending his head as men do when their enjoyment is in perspective rather than an actuality.

From beneath a stone a viper had raised itself, and seemed to salute the travellers with its forked tongue.

When the picture came into Mrs O’Sullivan’s hands, she fxed her spectacles and held it up a little to let the most light possible fall on it. Then she spoke —

‘God bless us and save us, but that’s an awful thing. Where did you see that, Mr Parnell?’

‘I never saw it, ma’am, except in my mind, and I see it there often enough. You, young men, mind the lesson of that picture, for it is truth. Death and the devil go together, and so sure as the devil grips hold of you, death is not far of, you may be sure, in some form or other, waiting, waiting, waiting.’

Mr Muldoon saw that the subject of drinking was coming in again, and said maliciously –

‘And this is all from a glass of beer.’

‘Ay, if you will,’ said Parnell. ‘That’s how it begins – that which is the curse of Ireland in our own time; and which, so surely as Irishmen will not use the wit and strength that God has given them, will drag her from her throne.’

Jerry got into the conversation:

‘One thing John Sebright tells me, that there is less drunkenness in England than here.’

‘Don’t you believe him,’ said Parnell. ‘That man means mischief to you. He wants to entice you to England, and then live on you when he gets you there. For Heaven’s sake put that idea of going away out of your head. You’re very well here as you are; and let well alone.’

Jerry’s mother spoke also. ‘John Sebright is a nice chap to quote sobriety as a virtue. Do you remember how often I gave you money to pay his fnes to keep him out of prison after his drunken freaks, for the sake of his poor dead and gone mother. Why, that chap could no more tell truth than he could work, and that’s saying a good deal.’

‘Well, drink or no drink, mother, England’s a grand place, anyhow, and there’s lots of money going there.’

Parnell rose up from his chair and said severely – ‘Jerry O’Sullivan, do you know what you are talking about? True, that England is rich, but is money all that a man is to seek after? If the good men leave poor Ireland to make a little more money for themselves, what is to become of her? Is it not as if she was sold for money; and if you look at the real diference of wages — the wages that good sober men that can work, get here and there, a poor price she would be sold for after all.’

‘I don’t like that way of putting it,’ said Jerry, rather testily. ‘In fact I have almost made up my mind to go, and I don’t think I’m selling my country at all at all, and I wish you wouldn’t say such things.’

Parnell said nothing for a few moments. Then he tore the picture out of his note-book and handed it to him saying –

‘Jerry, old boy, if you ever do go, keep that in your purse, and if ever you go to pay for liquor for yourself or others, just think what it means.’

When the party rose up to go they found that Katey had been crying quietly, and her eyes were red and swollen.

Jerry O’Sullivan’s home was happy, and his poor, good little wife feared a change.

CHAPTER 3

An Opening

Jerry O’Sullivan’s desire to go to England was no mere transient wish. As has been told, he had had for years a strong desire to try his fortune in a country other than his own; and although the desire had since his marriage fallen into so sound a sleep that it resembled death, still it was not dead but sleeping.

Deep in the minds of most energetic persons lies some strong desire, some strong ambition, or some resolute hope, which unconsciously moulds, or, at least, infuences their every act. No matter what their circumstances in life may be, or how much they may yield to those circumstances for a time, the one idea remains ever the same. This is, in fact, one of the secrets of how individual force of character comes out at times. The great idea, whatever it may be, sits enthroned in the mind, and round it gather subordinate wishes and resolves, as the feudal nobles round the King, and so goes on the chain down the whole gamut of man’s nature from the taming or suppression of his wildest passions down to the commonplace routine of his daily life.

And yet we wonder at times to see, when occasion ofers, with what astonishing rapidity certain individuals assert themselves, and how, when a strange circumstance arises, some new individual arises along with it, as though the man and the hour were predestined for each other.

We need not wonder if we will but think that all along the man was ready, girt in his armour, resolved in his cause, and merely awaiting, although, perhaps, he knew it not, the opportunity to manifest himself.

Whilst Jerry had been working – and working so honestly and well that he was on the high road to success – he never once abandoned in his secret heart the idea of seeking a wider feld for his exertion. Truly, Alexander has his prototypes in every age and country; and men even try to look ever beyond the horizon of their hopes, sighing for new worlds when the victories of the old have been achieved.

From the receipt of Sebright’s letter, Jerry had found the old wish reviving stronger than ever. He was so prosperous that the idea of failure in work seemed too far away to be easily realised; and his home was so happy that domestic trouble was absolutely beyond his comprehension.

The holy admonition – ‘Ye that stand take heed lest ye fall,’ should be ever before the minds of men.

Katey saw her husband’s secret wish gradually growing into a resolve, with unutterable pain; and tried to combat Jerry’s views but hopelessly. At frst he listened, and argued the matter over fairly in all its aspects, being ever kind-hearted and tender, and seeming to thoroughly sympathise with her views; but as the weeks wore on, he began to take a diferent tone, and without losing any of his kindness or tenderness to express more decided opinions and intentions. The change was so gradual that even Katey’s wifely love, and the acuteness which is the handmaiden of

love, could see no cause for change, nor could mark any time as being the period of a defnite change.

In fact, the masculine resolution was asserting itself over the feminine, and acting and reacting in itself, but constantly in the direction of settled purpose.

With the feeling of power which a man of average mental calibre feels over a woman of similar status amongst her own sex, comes a fuller purpose – a more decided, defnite resolve to the man himself. Thus, Jerry, whilst arguing with his wife, had been all the time strengthening his own resolve, and working himself up to the belief that immediate action was necessary to his success in life.

Wives, be careful how you argue with your husbands, for you walk on a ridge between two precipices. If you allow a half-formed wish to be the parent of immediate action on your husband’s part, without raising a warning voice should you see danger that he does not, then you do him a wrong which will surely recoil on your own head and the heads of your children. But if, on the other hand, you persistently combat with argument wishes which should be furthered or opposed with the patent truths of the heart’s experience, then you will surely fail, for you will be fghting reality with vacuity – opposing steel with air-drawn daggers of the fancy.

Katey’s position was very painful. She felt that her speaking to her husband was a duty which her wifely vow, as much as her wifely love, called on her to fulfl; but at the same time she felt with that subtle instinct of true love which never errs and never lies, that she was sapping the

foundations of her husband’s love and weakening the infuence which she had over him. Poor Katey! her lot was a hard one, but she felt – and she was right – that where duty points the way, then the way must be walked whatever be the misery of the journey, and wherever the road may lead.

Jerry’s mother, too, was fretted by her son’s determination. He never spoke of it to her, but she heard it from their mutual friends, and the very fact of his being reticent on the point caused her more pain by raising doubts as to his motive, not only for going, but concealing his wish from her. Jerry had a two-fold reason for his silence. Firstly, he did not wish to give her pain, and thought that by keeping silent on the point she would be spared at least the agony of looking forward to his departure. In this, Jerry, like many of his fellows, fell into the same error, which leads the hunted ostrich to hide its head in the sand – the error which we make when we think that shutting our eyes means shutting out the danger which we wish to avoid. Again, Jerry wished to avoid pain to himself.

The analysis of a sensual nature shows two evil qualities, which, although not always expressed, are, nevertheless, ruling powers – obstinacy and cruelty. No matter how these qualities may be counterbalanced by other qualities as good as these are bad, or no matter how well they are disguised, these two evil powers have here their home. Obstinacy in its hardest light is the adherence to a line of action begun for its end to be gained rather than for its duty; and cruelty is almost its logical consequence, for it is

by its direct or indirect means that obstacles are cleared away or points of vantage unworthily gained. Jerry’s nature was a sensual one, although it had ever been held in check.

The power of evil has a home in every human heart. In one it is a palace vast and splendid, so splendid and vast that to the onlooker there are no dark nooks, no gloomy corners, but where all is so rich and noble that there is dignity in everything. In another it is a shooting-box only visited for motives of pleasure. In another it is an ofice where gold and secrecy are synonymous terms. In another it is a villa. In another a lowly hut. In Jerry it was the last; but no one is to suppose that because it was a hut, that, therefore, it was unimportant. The residents in palaces are usually to a certain extent migratory, but the inhabitants of huts are seldom absentees, and every Irishman knows that a perpetually resident peasant is better for a country than a lordly absentee.

Thus Jerry’s devil, although living in a small house, was still always there, and was ever on the spot when opportunities occurred.

One change – one decided change – came which Katey regretted exceedingly, and that was in his friendship for Parnell. Hitherto the two men had been excellent friends, and Jerry’s success in some little business ventures was largely due to Parnell’s wise counsel. But now the two men were seldom together, and the elder one seemed to have lost all his old infuence over his companion.

Parnell saw the change as well as Katey, and was deeply grieved. He, however, saw, whilst he saw the change, what

danger there was in alluding to it, and so as he was one of those men who feel it almost as much a breach of duty to be silent on certain occasions as to bespeak falsely, wisely kept aloof and waited for a ftting opportunity for speaking earnestly to Jerry without the risk of ofending him.

Jerry, too, knew of the change in himself, and felt a sort of hostile indignation with all who opposed openly or tacitly his determination.

This was the frst manifestation of the cruelty of his nature.

His mother was broken-hearted, and in her grief, when arguing with him, unwisely gave play to her bitterness, and so hardened up one of the softest spots in his heart. She abused Sebright also, and, as some of the charges which she brought against him were manifestly absurd, Jerry took occasion to think, and to express his thoughts, that they were all absurd.

The devil works through love as well as hatred, and his blows are more deadly when we who strike and we who bear alike heed them not.

One day there came a letter from John Sebright, which infuenced Jerry vitally. It was as follows:-

‘Kingfcher Arms, Sundy.

‘Dear Jerry – You had better come over here at wanse, there is a place to sute you in a theatre called the Stanly, where the wants a carpentre to manage for them; he must be a good man or he won’t doo, and the wagis is fne, not to say exsiv, and the place esy and the people nice, you had

best tri for it at wanse, and don’t let the chance slip, or you will be a damd fool, and not worth gettin’ another, don’t let your mother or your wife keep you back, as the will tri to, for weemen isn’t able to do bisnis, but men is; an’ the maneger has a nefew, who is a friend o’ mine an’ a capatle felo, an’ a hed like iren, an’mony is goin’ heer lik water, an’ a man with your hed wood make a fortin in no tim, which let me no at wanse til I tel the nephew, which if you give me a £1 tu give him to speek for you, it will be all rite, and send the money by return to me, care of Mrs Smith, Kingfcher Arms, Welbred-street, London, and i remane yours trooly.

‘John Sebright.

‘P.S. – don’t sho this to your wif or mother, or the’l think i wance to mak you cum, an’ av corse mi motivs is disintrested, as i’m wel of miself an’ quit hapy.

‘P.S. 2. – if you tel the weemen tel them i’m goin’ to be marrid to a good woman ho is very pias an’ charetable an’ wel of don’t forget the £1.’

Jerry was no fool, and very clearly he saw through the motive of the writer of this precious epistle, but there were passages in it which interested him deeply. Notwithstanding the mean selfshness of the man’s thoughts, and the vile English in which they were expressed, he could not shut his eyes to certain things which they suggested, chiefy the opening as theatrical carpenter.

Jerry had never heard of the Stanley Theatre, and even now had not the ghost of an idea what it was like or of what class; nevertheless, he could not help thinking that it might be something good. London has a big name, and people who live out of it have traditionally an idea that everything there is great, and rich, and fourishing, and happy.

The people who live in it can tell a diferent story, and point to hundreds and thousands of the poorest and most wretched creatures that exist on the face of God’s beautiful world – the world that He has made beautiful, but that man has defaced with sin.

Jerry was in that state in which a man fnds everything which happens exactly suiting his own views. His eyes – the eyes of his inner self – were so full of his project that they were incapable of seeing anything but what bore on its advancement. He shut his eyes to dangers and defects and dificulties, and like many another man leaped blindly into the dark.

Sometimes to leap in the dark is the perfection of wisdom and courage combined; but this is when the gloom which is round us is a danger, from which we must escape at any hazard, and not when we make an artifcial night by wilfully shutting our eyes upon the glory of the sun.

Jerry wrote to Sebright, enclosing a Post-ofice order for one pound and telling him to lose no time about seeing after the situation for him.

He said not a word about what he had done, even to poor little Katey, who saw with the eyes of her love that he was keeping something back from her.

It was the frst secret of their married life, and the bright eyes were dim from silent weeping as the little wife rose the morning after the letter to London was despatched.

Several days elapsed before Jerry got any reply from London; and the interval was an unhappy time for both him and his wife. Katey’s grief grew heavier and heavier to her since she had no one to tell it to; and Jerry felt that there was a shadow between them. He recked not that it was the shadow of his own selfsh desire – the spectre of the future – that stood between them.

Katey’s lot was hard. The sweetest blessing of marriage is that it halves our sorrows and doubles our joys; and so far as her present life went Katey was a widow in this respect – but without the sweet consolation that married trust had never died.

Jerry’s anxiety made the home trouble light. He had, like most men to whom the world behind the curtain is as unknown as were the mysteries of Isis to a Neophyte, a strange longing to share in the unknown life of the dramatic world. Moth-like he had buzzed around the footlights when a boy, and had never lost the slight romantic feeling which such buzzing ever inspires. Once or twice his professional work had brought him within the magic precincts where the stage-manager is king, and there the weirdness of the place, with its myriad cords and chains, and traps, and scenes, and fies, had more than ever enchanted him.

The chance now ofered of employment was indeed a temptation. If he should be able to adopt the new life he

would have an opportunity of combining his romantic taste and his trade experience, and would be moreover in that wider feld for exertion to which he had long looked forward.

And so he waited with what patience he could, and shut his eyes as close as possible to the growing miseries of his home.

At last a letter came from Sebright, telling him that he had got the place, and one also from the manager, stating that he would have to be at work in a fortnight’s time, and stating the salary, which was very liberal.

Face to face with the situation, Jerry found that the sooner he told his wife the better. He took the day to think over his plans, and when he went home in the evening he went prepared to tell her.

There was about him a tenderness unusual of late – a tenderness which reminded Katey of the frst days of their married life and of the time when her frst child was born; and so the little woman’s heart was touched, and woman-like she could not fear, nor even see troubles in the light of her husband’s smile. Jerry himself felt the change in her manner, and his tenderness grew. He took her on his knees, as in their old courting days, and a few sweet whispered words brought the colour to her cheek, and the old light into her eyes. Then it was that Jerry felt how hard was the news which he had to tell, and he half repented of his resolution. He thought of the happy home which he was breaking up, and of the anguish of the little wife and mother who was to be taken away from all her friends and

relatives to begin the world anew amongst strangers. But the time was come when he must speak, for to delay would be cruel, and so he began with a huskiness in his throat which was not usual to him. ‘Katey, dear, I’ve some news for you.’ Katey’s arms tightened round his neck. ‘Oh, and good news too, Jerry, I know by your tenderness to me to-night. Jerry dear, have you given up the wild idea?’

Jerry did not expect this, and his voice became a little harder as he replied –

‘No, I have not given up the wild idea, as you call it. It is about it that I want to speak.’

Katey felt the shadow pass between them again, and in spite of all she could do her eyes flled with tears. She did not wish to hurt Jerry, however, and turned away her head. But, man-like, he would know all that was going on in the mind of his companion, and, taking her face between his strong hands, he turned it up to the light. As he did so, he saw the tears and could not help feeling annoyed, for he knew that as yet in the conversation he had said nothing to warrant the change from sunshine to rain. So he spoke not unkindly – ‘Cryin’ already. Ah, Katey, what do you mean?’ ‘Nothin’, Jerry, nothin’, my dear, only I couldn’t help it. I’m not very strong yet.’ She said this with a tender, half shy glance down at the cradle, which she was rocking with her foot, that would have turned the heart of a savage.

Jerry could not help feeling moved, and clasped her still more tenderly in his strong arms, and his voice softened –

‘Sure, Katey, it’s breakin’ my heart I am all day knowin’ how you would take the news. Cry away, darlin’, it’ll do you

good, and mayhap the news will make you cry.’

‘No, no, Jerry, only talk to me like that, and I’ll never cry – never – never – never.’ The little woman’s voice went up in a sweet, half playful crescendo as she reiterated the last words, and shook aside her tears.

‘Then, Katey, I’ll tell you. I have got an ofer to go to England’ – Katey’s face fell – ‘to London – to become head carpenter in a theatre, an’ I’ve written to say I’ll take it.’

Woman’s nature, when compared with man’s, resembles more the hare than his does, and her moral eye, like the hare’s eye, is set far back for seeing the past clearly, whilst it accepts the future blindly. She accepts facts more easily than resolves; and when once a thing has been accomplished, and any fnal or decisive step taken, the major part of her anxiety is over. Accordingly Katey heard her husband’s resolve with an equanimity which took him by surprise. She did not cry, although her heart felt to herself to sink into her very boots, but simply drew his head on her bosom and stroked his hair, saying fervently –

‘God grant, Jerry, acushla, that it may be for the best. May all the saints pray for us both.’

‘Amen,’ said Jerry, and then both remained silent for a time.

Soon the woman’s curiosity spoke, and her imagination began to work; and in the pleasure of expectation of change – always specially dear to women – she lost sight for a time of her present trouble. She began to question Jerry about the new engagement, and, having once began, poured forth such a tide of questions that he had no time to

answer them, even had he known himself all she wanted. He did as well as he could, however; and now that the worst of the news was over, her hopeful nature took the brightest view possible of the case, and she seemed, by comparison with her mood of the last few days, quite happy.

Jerry did not tell her that night of the time of leaving, but let her sleep with what happiness she could, for he knew that the morrow, when she had learned the necessary suddenness of their departure, would be a sad one for her.

In the morning he told her just before going to his work, for he put of the evil moment, half that she might be able to have her cry in quietness – he knew that she would cry – and half with a man’s selfsh wish to avoid an unpleasant scene.

Katey bore up till he was gone, and then the tide of her grief and sorrow burst forth unchecked, and she cried so pitifully that her little ones began to cry from childish sympathy. She took them in her arms and knelt down with them and rocked herself and them to and fro, and moand – ‘Oh, woe the day, oh, woe the day.’

CHAPTER 4

The New Life

Jerry O’Sullivan well knew the diference between the dispositions of his wife and his mother; and it was not without a shrinking of spirit that he approached the dwelling of the latter that evening to impart the unwelcome news.

His fears were not without foundation, for when he began to tell his news the old lady who had hitherto been full of love and afection broke out into a desperate ft of crying, a very unusual thing with her, mingling her tears with reproaches such as Jerry had never before heard from her lips.

‘And you, my son,’ she said, ‘are about to leave your home, and your country, and your mother, and to go amongst strangers. Oh, woe the day, oh, woe the day, that my child ever wants to leave the ground where his poor dead father lies sleeping. Oh, Jerry, Jerry, was it for this that I watched over your youth, and toiled and slaved for you, early and late, that when I saw you grow into a strong, steady, honest man, with a sweet wife and a happy home, I should see you leave me for ever.’

Jerry interrupted. ‘Not for ever, mother.’

‘Ay, ay, for ever. Wirrasthrue, wirrasthrue. Sure, don’t I know I’ll never see your face again. You’re goin’, Jerry, among strangers an’ their ways are not our ways, and amongst them you’ll forget the lessons of your home. You’re

goin’ to a city where the devil lives, if he lives any one place in the world; and I must sit at home here and doubt, and sigh, and weep, and weep, till I die.’

‘Mother, dear, don’t take on like this. Why should you doubt, and sigh, and weep at all, at all? I amn’t goin’ to do anything wrong. I’m goin’ to work harder than ever, an’ I think, mother – I do think that it’s not fair to me to think that I’m goin’ to go to the devil, just because I leave one town to live in another.’

But reason and consolation were alike thrown away on Mrs O’Sullivan. The spice of obstinacy in her nature, and which Jerry had inherited from her, made her stick to her point; and so after many eforts Jerry came away leaving her bowed down with sorrow. He was himself somewhat indignant – and with fair enough reason – that all his relatives should take it for granted that he was going to change an honest hardworking life for an idle dissolute one.

He did not like to go home at once, for he somehow felt afraid of meeting a reproachful look on Katey’s face. This fear was a proof that he knew in his secret heart that he was doing wrong, for in all their married life Katey had never once given him cause for such a thought; it was in his own conscience that the reproach arose; and the look was on the face of his angel.

Accordingly, he made a detour and called at the house of Mr Muldoon. The great man was within and received him heartily.

‘Why, O’Sullivan,’ said he, ‘this is quite unexpected. Sit down, man, and make yourself comfortable.’

Jerry sat down, but was anything but comfortable. Whilst he was on the way to his home, he had felt a desire to stay away, but now that he was settled down he longed to be at home. Katey’s face, pale with her recent sickness, and paler still from her recent grief, seemed to look at him, and he thought and felt how her poor heart must be beating as she waited and waited for his return, counting the minutes, and fnding in each moment’s extra delay new causes for dread. At last he could stand it no longer and jumped up, saying to his host:

‘I can’t stay. I have not been at home yet, and Katey will be expecting me.’

Muldoon laughed.

‘There’s a man with three children! Sure, a wife in her honeymoon wouldn’t look for you like that.’

‘Katey would, and does. No, indeed, I can’t stay. I just came to tell you that I have got an engagement in the Stanley Theatre, in London, as carpenter, and I am going in less than a fortnight.’

Mr Muldoon whistled.

‘This is sudden,’ he said.

‘Ay,’ said Jerry, but said no more.

‘You must come and spend an evening with me before you go, and your mother will come and Marg-, Miss M’Anaspie; and we’ll get the boys and girls and have great fun.’

‘Agree,’ said Jerry, and took his leave.

When he got home Katey few to the door to meet him, and clung to him and kissed him, and he wondered how he

could be such a fool as to stop away for fear of any reproach from her. He told her of his visit to his mother and Mr Muldoon, and of the invitation of the latter, which she agreed should be accepted.

The next week was such a busy one that neither Jerry nor Katey had much time for repining, and even Mrs O’Sullivan found some consolation in her exertions and the liberal preparations which she was making for her son’s departure. At frst there was some question as to the advisability of Katey and the children going at once, as some of the family thought that it would be better if Jerry went alone and Katey waited to follow when all was comfortably settled for her. Katey herself had, however, put a stop at once to the discussion.

‘I don’t want comfort,’ she said, ‘and I amn’t afraid to rough it since we are to go; but I want to be with Jerry.’

Her mother-in-law backed her up in this view, and so the matter was arranged.

Mr Muldoon’s entertainment was a great afair. No expense had been spared on the host’s part, and no trouble on the part of his servant; and the consequence was an amount of splendour which dazzled all beholders.

The entertainment was given in the drawingroom over the shop, a room seldom entered save by the servant, who periodically dusted it. The covers had been taken of the chairs which now showed their red cushions in all their splendour. The yellow gauze had been removed from the mirror, the picture frames, and the gaselier, which no longer presented its habitual appearance — that of an

immense jelly bag, through which yokes of egg have passed. The eating and drinking was on a scale of magnifcence. Not only had the warehouse been ransacked for its delicacies, but good things of, so to speak, an alien description had been provided, and so far as the inner-man was concerned nothing was wanting. The company was the same as that at the christening party, with the addition of a couple of hard dry old men, of whom Mr Muldoon thought much, and to whom he paid decided deference.

When all the company had assembled, which was about seven o’clock, Mr Muldoon ordered supper, and all went vigorously to work. Hitherto there had been a little stifness. Price and Carey had been somewhat awed by Mr Muldoon’s magnifcence, and their sweethearts, seeing this, had followed their lead, and remained in seemingly bashful silence. Jerry and Katey, and Mrs O’Sullivan, and Parnell, were too heavy-hearted for mirth, and so the only members of the party who were lively, were the host and Miss M’Anaspie.

The latter was anything but sorrowful, and truly with good cause. She saw with the instinct of her sex that she had made a conquest in the rich old bachelor, and already tasted possession of all the splendour which surrounded her. She was even now, whilst she pretended to admire, planning changes in the room and its furniture. The chairs would not be arranged as at present, the pictures were too gloomy, and would have to be replaced by others of brighter hue – in fact, altogether much additional splendour would have to be imported, so that all her friends and

visitors would be driven to the wildest envy without giving them a chance of escape.

When the supper was done, Mr Muldoon stood up and made a speech reverting to Jerry’s departure, and wishing him success, and also managing to bring in a neat compliment to Miss M’Anaspie’s good looks, which caused that bashful young female to hide her face in her pockethandkerchief and to giggle for some minutes. Before he sat down he said, and said it pointedly –

‘The last meeting of a festive description at which we all assisted was, I think, somewhat spoiled by various discussions. Now, I hope that to-night we will have no such discussions. I wish that our friends, Jerry and Katey, may have an evening all jolly and merry.’

‘Hear, hear,’ said the old men, simultaneously.

Parnell felt that all this was levelled at him, and found his hands tied. There was no discussion of any kind, and as nothing more than casual remarks were made, the party soon took a tone so gloomy that even the lively Margaret found her spirits below zero. All this tended to irritate Mr Muldoon. A man of his temperament gets dogmatic in proportion to his irritation, and consequently he soon was laying down the law on every imaginable point.

This still more increased the gloom till all was so deadly that Katey could bear it no longer, and left earlier than she had intended. The rest were not slow to follow her example, and Mr Muldoon was so enraged at the miserable failure of his merry party that he would hardly say good night.

The days drew on towards their departure, and all were so busy that there was no time for thought – perhaps just as well for those of them that had hearts to feel.

At last the day arrived, and their friends assembled at the North-wall to see them of, for they were going by sea on account of their luggage, which was quite disproportionate to their rank in life. The anguish of parting was very great, and the tears shed many. But partings must ever be, and this one was like all that have gone before and all that are to follow after. So great was the grief of all that Jerry for a time repented of his determination.

And so Jerry O’Sullivan and his wife and children left home and fortune to seek greater fortune in a strange place.

The voyage lasted three days. For the frst twenty-four hours Katey was too sick to think, and the poor children sufered dreadfully; and it was not till the black bare rocks of the Land’s End came into view that the poor little woman was able to look about her. Even the frst glimpse of her future country was not reassuring, for it looked very black and cheerless and inhospitable indeed.

However, by the time Falmouth, with its houses clustered up the hill, and its quaint, quiet, old-world look still upon it, came in sight, her spirits rose. From thence the journey was enjoyed by all, for the weather was fne and the sea like glass. The south coast of England is full of charming scenery, which one sees much of in passing from port to port, and it was no wonder that Jerry and his wife felt

somewhat elated at being amongst such wealth and security as the disposition of things there presupposed. Plymouth, the queen of ports, with its wealth of naval strength and its picturesque batteries on Mound Edgecombe, Drake Island, and the Hoe; and Portsmouth, guarded by iron-clad towers out in the very sea, miles of continuous batteries and innumerable war-ships, made a deep impression, and somehow Katey felt that Jerry was a cleverer man than she had given him credit for being.

It is the nature of the greater to absorb the lesser. We see the beauty of the rose in full luxuriance in the summer sunlight; it is only when we reach the core that we fnd the canker worm.

At last the Thames was reached, and the O’Sullivans were fairly awed by the strength of the defences. All up the river, which took them the best part of a day to ascend, the banks were studded with forts on either side. Little low-lying forts, all fronted with iron, dangerous places, very hard to hit from any distance away, but able to contain the best and biggest guns made in the world; the black iron-cased ports, in rows seemingly level with the water’s edge, looked like the iron doors of the vaults in a cemetery, a fact which, in the eyes of the onlookers, added not a little to the grim terror of their appearance. The wonder culminated at Tilbury, for here two immense forts defended the narrowest part of the river, and made the idea of any hostile force passing up it a complete impossibility.

London was reached at last. Busy, bustling, rushing, hurrying London, compared with which all other cities

seem as the castle of the sleeping princess in the fairy tale; and Jerry and his wife, on landing from the steamer, albeit they came from a city where Progress speaks with no puny voice and works with no lazy hand, felt bewildered.

At the best of times and places a landing-stage is no fower garden, especially to the incomer; but the London landing-stages, with their great steam-cranes and palatial warehouses, and ships lying seven or eight deep out into the river, are wonders in themselves. It was only by patience, and care, and asking many questions that Jerry was able to bring his family into the wholly terrestrial world.

Through much bustling, scrambling, and exertion, they found their way into the street where the theatre was situated, for as they knew nothing about the place Jerry thought it best to get as near to his work as he could. He had high resolves, and intended to work harder even in the new life than in the old.

The neighbourhood was exceedingly poor, and an amount of misery and squalor prevailed which showed Katey in as many moments as the other had taken hours that all was not gold which glittered within the strip of silver sea which her sons call Britain’s bulwarks, but that the greatness, and wealth, and strength, have their counterfoils in crime, and poverty, and disease.

More than an hour was spent in looking for lodgings, and Katey’s heart was sick and sore. There was some vital objection to every place. One was too dear, another was too dirty, a third was too small, and so on.

All things have an end, even looking for lodgings, and towards nightfall they lighted on a place, which, although not exactly what they required, was still the nearest approach to it that they had yet come across. It was over a green-grocer’s shop, and promised to be fairly comfortable. Katey, somehow, felt that the mere show of green stuf gave it a little of the idea of home – just enough, she found out afterwards, to make her home sickness, which had worn somewhat away during the last day or two, come back again.

However, she had no time for brooding over sorrows, real or sentimental. The children were dead tired and crying with sleep, and so when a fre was lit, and the basket of provisions opened, they were tucked into their bed and fell asleep in a moment.

Whilst Katey was thus attending to her household duties, Jerry was exercising his professional skill in making the room comfortable, knocking up nails here and there, and generally improving the disposition of afairs. Both had fnished about the same time, and then Katey made the tea, and the husband and wife sat down to chat, she sitting on his knee as all loving little wives love to sit.

Jerry now felt face to face with the realities of his new life, and the prospect was not all cheering. He missed the comforts of home, and felt, in spite of his strong wilful self-belief which deadens a mind like his to many outward miseries, that he was but an atom in the midst of the world around him – a grain of sand in that great desert which men call London. Katey was more cheerful, for a wife carries

with her husband and children her true home which rests as securely in her heart as a snail’s-house on his back. Katey slept that night, for she was tired out, but Jerry could not sleep.

In the morning he was stirring by daylight, and after lighting the fre, for Katey was so worn out that she still slept, went out to look about the neighbourhood. It was still so early that but few people were up. He found his way to the theatre, whose external appearance flled him with consternation. The outside of a small theatre is at the best of times unpromising, and this one looked, in the cool morning air, squalid in the extreme.

Jerry wandered round it curiously trying to get every possible view. As it went back into a large block of buildings, this was no sort of easy task; and so by the time the survey was completed he was quite ready for his breakfast.

Katey was up and as bright as a bee. The children had recovered their good temper in their sleep, and everything was infnitely more cheerful than had seemed possible for it ever to be the night before.

Katey came up to her husband as he entered the room and put her arms round his neck and kissed him several times very, very fondly.

‘God bless our future life, Jerry, dear,’ she said, ‘I hope it will always be as happy as this. If I can do it be sure your home will always be a cheerful and happy one.’

He kissed her in return, feeling more deeply than he cared to say, for there was a rising lump in his throat.

The morning passed in settling things straight, and in the afternoon Jerry went down to the theatre again. The place looked more lively than before, although in reality still very dismal. There were a few of those nondescript, ill-clad loungers that are only seen in the precincts of theatres, hanging round the door – those seedy specimens of humanity who are the camp-followers of the histrionic army.

When Jerry asked one of them where he would fnd the manager, he winked at his companions, rubbed his lips, and said, with obsequious alacrity –

‘This way, sir. Come with me and I’ll show you the way.’ Jerry followed him through several dark passages flled with innumerable boxes of all sizes – old woodwork and portions of scenic ornamentation half covered with tarnished gilding, till they reached a door, to which the

guide pointed, saying –

‘It’s a very dry day, your honour.’ ‘Very dry,’ said Jerry.

‘A drop would not be bad, sir.’

Jerry’s appearance was so good that the man called him sir, not all for the purpose of fattering his small vanity.

Jerry gave him twopence, and knocked at the door.

He was told to come in, and on doing so found the manager who was just going out, and who, being in a hurry, told him to come to him next morning to talk over his duties, and in the meantime to see the stage-manager, Mr Grifin, who would show him over the place, so that he might get accustomed to it.

Jerry managed to fnd his way to the stage, which was lit by a great line of gas-jets on the top of a vertical pipe, like a hayrake, stuck at the back of the orchestra. A dress rehearsal was going on, and Jerry stood in the wing to watch. The play was a version of Faust, and the dresses were the same as those used in Gounod’s opera. Presently, Mr Grifin noticed the strange face, and came over to the wing. Jerry told him his name, and was at once welcomed as a member of the staf. He was introduced to several people on the stage with whom he was likely to come in contact. Amongst the actors was a tall individual who was performing the part of ‘Mephistopheles,’ who came over to Jerry and introduced himself, saying that he knew John Sebright. Jerry was glad to see anyone who had the tie of a mutual friend amongst so many strange faces, and, although he did not like the appearance of his new friend, spoke to him heartily.

Whenever he had an opportunity during the course of the rehearsal he came over to Jerry and resumed their chat. Presently he came over and said –

‘I am not on in this scene. Come and have a glass of beer with me.’

‘With pleasure,’ said Jerry, for he was hot and thirsty, and the twain adjourned to a little tavern across the street, Mons, the new friend, calling into his dressing room to put on his Ulster coat, so that his stage dress would not be observed.

When they entered the tavern the bar-keeper was busy settling his glasses, and had his back turned to them. Mons

took of his Ulster and sat down, there being no one but themselves present except a drunken shoemaker, whom Mons knew, and a beggarman who followed them in.

When the bar-keeper turned round Jerry met the most repulsive face he had ever seen – a face so drawn and twisted, with nose and lips so eaten away with some strange canker, that it resembled more the ghastly front of a skull than the face of a living man. Jerry was shocked, but in the meantime Mons called for the beer, which was brought and soon drunk.

Mons then said —

‘Grinnell, this is our new carpenter.’

‘Glad to see you, sir. Welcome to London. I understand you’re Irish. You beat us there in one thing, at all events.’

‘What is that?’ said Jerry.

“Your whisky. We can get none like it; but I tell you what, I’ll give you some liquor you never tasted, I’ll be bound. And as you’re a stranger I’ll make it a present to you.’

‘No, no,’ said Jerry.

‘Take it,’ whispered Mons. ‘He’ll be ofended if you don’t.’

Grinnell produced a bottle of labelled ‘Gift’ from the shelf, and poured out two half tumblers full and handed one to each.

‘That’s what I give for my hansel,’ said Grinnell. ‘What do you think of it?’

‘Capital,’ said Jerry, after tasting it. ‘What is it called. I see ‘Gift’ on the bottle?’

‘No, that’s not its name. I put that on it to show my customers that when I give it I mean civility and not commerce. It’s a decoction I make myself.’

Just then a boy ran across from the theatre and said – ‘Mr Mons, you’re wanted. Your scene is on.’ Mons tried to put his hand into his pocket, but could not as his tights had no pockets. He said to Jerry as he went out – ‘I’ve got no money with me. Will you pay for the beer and I’ll give it you when you come back to the theatre.’ ‘All right,’ said Jerry, and he took out his purse. As he opened it he saw Parnell’s picture, and then it struck him that his new life was beginning but badly, drinking in the middle of the day.

He paid the money and went quickly out of the public house without looking behind him.

CHAPTER 5

How The New Life Began

When Jerry got back to the theatre the place did not somehow look the same; there was too much tarnished gilding, he thought, and too little reality. Although the place seemed very old and dirty – so old and so dirty that after looking about him for a little time he felt that there was room and opportunity for all his skill and energy – there was something so cheering in this prospect of hard work that he forgave the dirt and the age, and longed to get into active service.

The rehearsal did not take much longer, and then the various actors and employes dispersed. Mons came over to Jerry and asked him to come to his dressing-room for a moment. Jerry was anxious to get home, and said so.

‘You need not fear,’ said Mons. ‘I shan’t detain you a minute. I only want to give you what you paid for me.’

‘Nonsense, man,’ said Jerry, who felt almost insulted, for, like all Irishmen, he had one virtue which too often leans to vice’s side – generosity, and considered that hospitality was involved in the question of ‘who pays?’

Of all the silly ideas that ever grew in the minds of a people, feeding on their native generosity of disposition, this idea is the most silly. Let any man but think honestly how honour or hospitality can be involved in the mere payment of a few pence, and then ask himself the question in his heart of what diference there is to him between the

nobler virtues of his soul and the pride of superabundant coinage. Jerry O’Sullivan was no fool, and often reasoned with himself on the subject; but still the prejudice of habit was too strong within him to be easily overcome, and so he felt hurt in spite of his reasons. Mons answered him suavely —

‘No nonsense at all. I borrowed a small sum of money of you, which you kindly lent me. I now wish to repay you.’

‘Sure there isn’t need of repayment because I paid for a glass of beer.’

‘But a debt is a debt, large or small, and I don’t want to remain due to any man.’

Jerry thought for a moment or two. The justness of the statement struck him so forcibly that he felt that any further talk would be unfair to his friend; so answered simply – ‘Fair enough,’ and took the money profered, thinking to himself what a good-hearted, honest fellow his new friend was.

It was well nigh dark when Jerry got home. He found Katey up to her eyes in work; for between settling the rooms and unpacking, and looking after the children and the supper, she had quite enough to do. She had given the rooms a thorough cleaning – a thing very much required — and as they had not quite recovered from the efects; were not so comfortable as they might have been. The foors still presented that patchy appearance which newly-washed woodwork always assumes; and even the bright fre was not able to quite overcome the idea of damp thus suggested.

Nevertheless, the change even to unfnished cleanliness was pleasant after the unutterable grime of the theatre; and Jerry felt how pleasant was the idea of home, albeit he regretted in the core of his heart that his real home – the place where he was born and bred — was far away.

Katey bustled about; and soon the supper was ready, and in its consumption things began to assume a pleasanter aspect. All were tired and went to bed early.

In the morning Jerry was up early and round the neighbourhood looking about him. Theatrical life, save on occasions, begins late, even for the subordinates, and Jerry’s services were not required till an hour which, when compared with his habitual hour for going to work, seemed to him to be closer to evening than morning. At the time appointed he was waiting to see the manager, who did not appear, however, till more than an hour after his engagement. Jerry waited with impatience for his coming. To a man habitually as well as naturally active in occupation, nothing is so tiresome as that of waiting: it is only the drones in the hive of life that enjoy idleness in the midst of others’ work.

It is the misery of all those whose work is connected with the arts that there is a spice of uncertainty in everything. It would seem as if Providence had decreed that those who soar above the level of commonplace humanity should bear with them some counterbalancing weakness to show them that they are but of the level after all. The ancients showed this idea by an allegory in the story of him who, with wings of wax, thinking himself no longer a mortal, but a god, few